For a garden, garden stones play an important role in enhancing the landscape. Those strategically placed in key areas of the garden are called kaiseki landscaping stones, while combinations of several stones are referred to as ishigumi stone arrangements. Stones used as paths on the ground or near the waterfront are known as shikiishi paving stones or isowatari rocky paths, among other terms. These stones are admired for their natural colors and beautiful shapes. On the other hand, processed stones such as water basins and stone lanterns add an element of elegance.

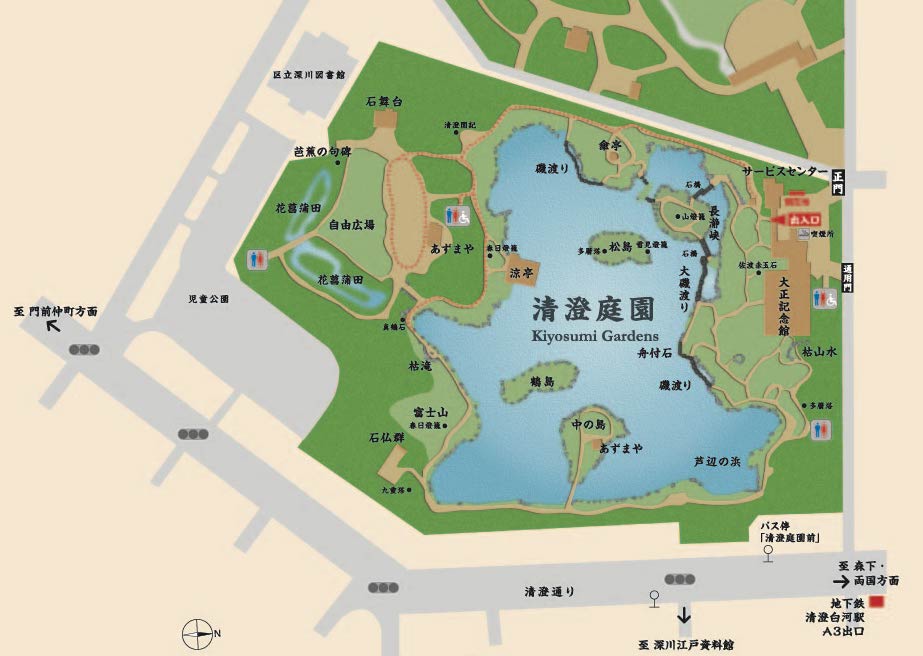

In Kiyosumi Gardens, more than 50 landscaping stones are densely placed along the garden path. One reason for this, I believe, is the reduction in garden space following the Great Kanto Earthquake. It is possible that the stones are arranged not only to create a landscape but also to showcase the pride of the stone collection.

Let’s explore some of the most distinctive stones in Kiyosumi Gardens while listening to Atsuko Shigeno, the center’s director, and Naoo Inoue, the deputy director, discuss their work.

Kiyosumi Gardens (Part 2)

In Search of Tokyo Serenity

No.006

Kiyosumi Gardens is a renowned stone garden constructed by the Iwasaki family across three generations. Apart from the breathtaking Daisensui pond and lush greenery, the unique stones collected from various regions by Yataro Iwasaki are also a sight to behold. In the second part of the article, we will explore the allure of these stones that have become synonymous with Kiyosumi Gardens, accompanied by commentary from Miho Tanaka and photographs taken by Norihisa Kushibiki.

Photo: Norihisa Kushibiki

Story: Miho Tanaka (Curator at Edo-Tokyo Museum)

Cooperation: Tokyo Metropolitan Park Association

What is a stone in Kiyosumi Gardens?

Yataro’s beloved venerable stones

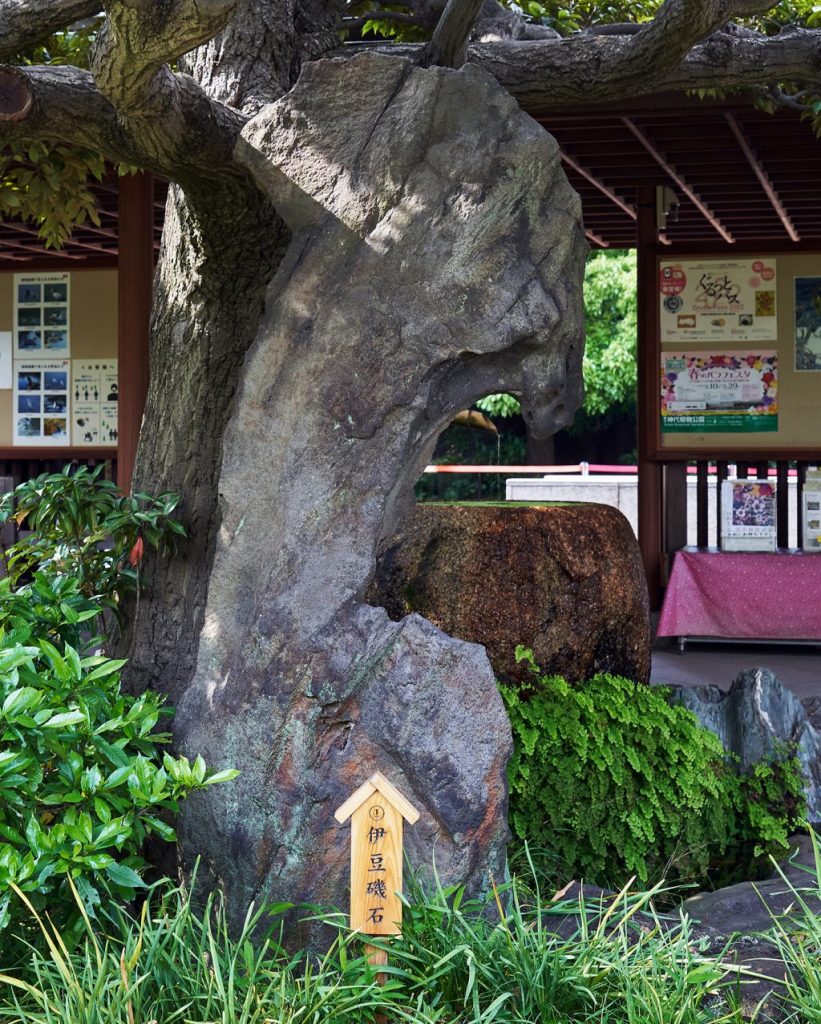

Near the entrance, there is an unusually shaped stone known as Izu Isoishi. Its surface bears small irregularities caused by wave erosion, lending it a powerful presence that captivates the beholder.

In the background, you can spot a natsume-shaped water basin crafted from a stone called Settsu granite. It bears the scars of the Great Kanto Earthquake, with scorch marks and areas that were stripped away, telling the poignant story of the garden’s history. Adjacent to the rounded brown water basin, vibrant green ferns grow in perfect harmony, creating a balanced scene.

As the name suggests, Sado Akadamaishi is distinguished by its vibrant red color. This precious stone, mined on Sado Island in Niigata Prefecture, is no longer available due to being extensively extracted. The one in Kiyosumi Gardens is said to be a masterpiece with exceptionally rich coloration. This red color is derived from iron within a rock variety called chert, which forms through the accumulation of deceased microorganisms.

Soshu Kajiyaishi, produced in Kanagawa Prefecture, is a rare stone used as a garden stone. It is hardened by the presence of small pebbles and features a rocky surface resembling ripples, further accentuated by the softness of moss that grows upon it.

“The moss tends to flourish even more during the rainy season,” says Mr. Inoue, the deputy director of the center.

While stones are often regarded as symbols of constancy, it is interesting to appreciate the changes brought about by the growth of such plants.

My favorite is the Manazuruishi. It is strategically placed to conceal the sluice gate on the south side of the garden and shows pockmarked spots on its smooth surface.

The stone gets its name from the town of Manazuru in Kanagawa Prefecture, where it is sourced, and it also bears a resemblance to a lion. The right side represents the head, the pattern in the center resembles a majestic mane, and the elongated portion signifies the tail. It is delightful to appreciate these features and interpret them in your own way.

This water basin, named Mizubore, is made of Hozugawaishi sourced from Kyoto. The water-receiving part is a depression formed by the flow of water, where stones have carved out a hole (pothole) over time. Hozugawaishi possesses a natural hardness, but it has taken shape over an extensive period.

“Due to its inconspicuous placement, it often goes unnoticed, so I encourage visitors to seek it out during their visit,” says Ms. Shigeno, the center’s director.

Similarly, stones like Ikomaishi from Nara Prefecture and Bicchu granite from Okayama Prefecture were collected from the Kansai region, while Sanuki granite from Kagawa Prefecture and Iyo Aoishi from Ehime Prefecture were sourced from the Shikoku region.

From “Tokyo Vintage Gardens”

Another unique feature of Kiyosumi Gardens is the presence of three isowatari rocky paths that extend out into the pond. There is also a large monument inscribed with Matsuo Basho's famous haiku, “Furuikeya kawazu tobikomu mizuno oto” (you can hear the sound of a frog leaping into an old pond). Basho is an Edo-Period poet who is associated with Koto-ku. Located in Koto-ku, which is closely associated with Basho, Kiyosumi Gardens offers “parent-child haiku classes” and other activities.

“There are rules and patterns governing the placement of the stones, with various considerations taken into account, such as determining which side of the stone faces the parkway. However, even if you don’t want to do that, I want you to enjoy the stones freely, looking at their texture or using them as something,” says Mr. Inoue, the deputy director of the center. To love the garden is, in a way, to love the stones.

A visit to Kiyosumi Gardens, renowned for its famous stones and uniquely shaped rocks, is also recommended on rainy days. When wet, the stones darken in color and reflect the light, enhancing the garden’s allure and providing an even more captivating experience.

In addition to Kiyosumi Gardens, another garden donated by the Iwasaki family to the city of Tokyo is Rikugien.

I am impressed by the philanthropic spirit of the industrialists of that era, who invested their private fortune to create gardens and later returned them to the public.

Japanese original text: Yasuna Asano

Translation: Kae Shigeno

Kiyosumi Gardens

Location: 3-3-9 Kiyosumi, Koto-ku, Tokyo

Hours: 9:00 a.m-5:00 p.m. (Last admission: 4:30 p.m.)

Closed: year end and New Year holidays

Admission: 150 yen for adults, 70 yen for individuals aged 65 and over

https://www.tokyo-park.or.jp/park/format/index033.html#googtrans(en)

*Please check the official website for opening information before visiting.

Norihisa Kushibiki

Photographer. Born in Hirosaki, Aomori Prefecture. Active mainly in the fields of advertising and editorial work. Provides portrait photography for numerous celebrities and prominent figures. Took private photos of Giorgio Armani and Gianni Versace. His work as an official photographer of the nine Tokyo metropolitan gardens inspired him to continue taking photos of traditional Japanese-style gardens as his life’s work.

Miho Tanaka

Curator at Edo-Tokyo Museum. Provides explanations of historical materials and delivers lectures on the theme of the relationship between people and flora, and specifically the art of gardening, during the Edo period. Tanaka conducts a course “Traditional Japanese Gardens x Area Guide,” which explores the history of classical gardens in Tokyo from the perspective of local characteristics.