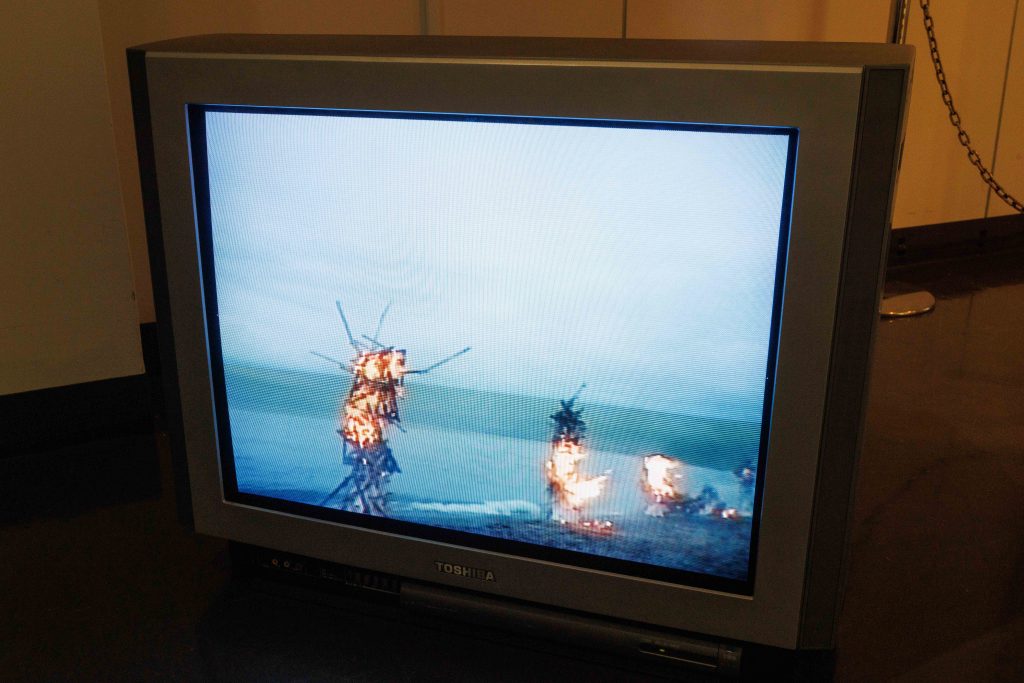

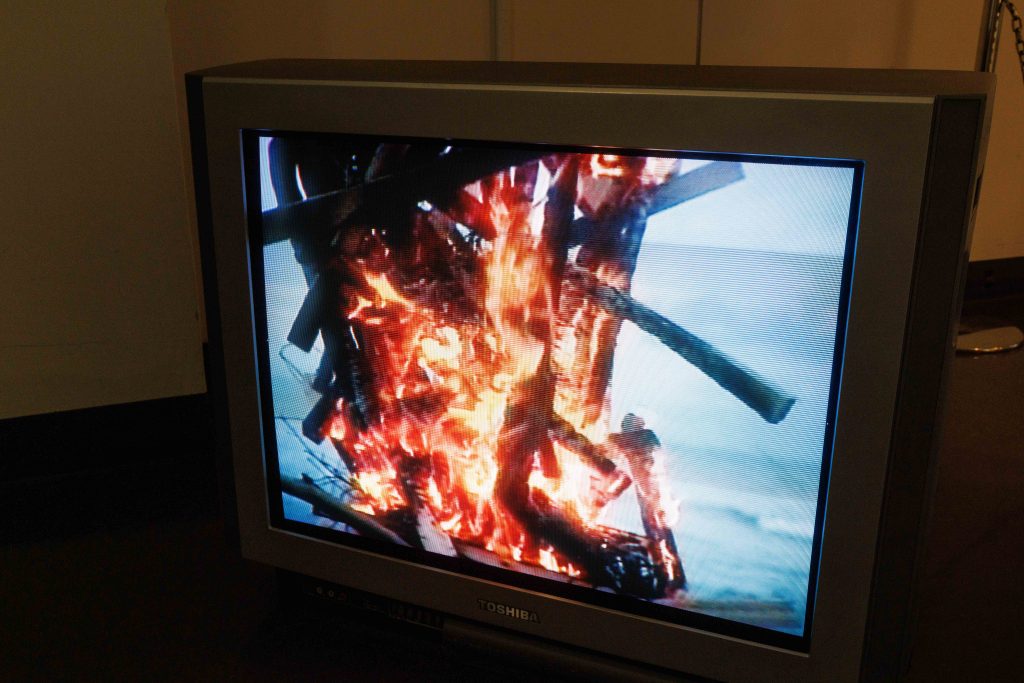

The “Shigeo Toya: Sculpture” exhibition was jointly held by two prefectural museums in Nagano where Toya was born, and in Saitama where he is currently based. The exhibition at the Saitama venue consisted of three parts, tracing the artist’s journey over half a century, from the sculpture of human body he created as a university student to the POMPEII ... 79 Part 1 presented at his first solo exhibition, his representative “Woods” series, and his latest Body of the Gaze series.

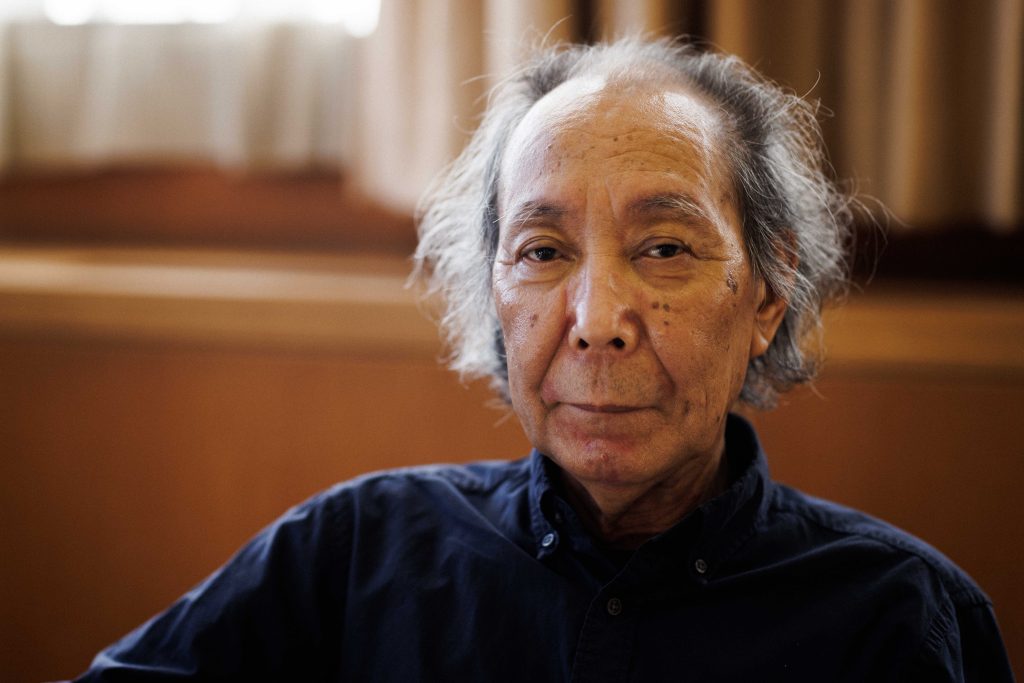

──You have exhibited your graduation works and other works from your university days. How do you feel when you see them now?

Toya I have mixed feelings. I did figurative art for four years in university and moved to abstract art in graduate school, but the idea of transitioning towards contemporary art had been brewing since my undergraduate days, and I was experimenting with it alongside figurative art.

The sculptures from my student days remind me of the historical context of that time. During my university years, the Vietnam War was nearing its end, and there was intense student activism due to the 1970 Anpo Protests, often resulting in clashes with riot police on campus. In such a charged atmosphere, students were forced to grapple with their ideological stances and determine their course of action. The sculptures from my student days serve as self-portraits reflecting that period in my life.

──In 1970, the exhibition “Between Man and Matter (The 10th International Art Exhibition of Japan)” was held, in which many Mono-ha artists also participated.

Toya I went to see it. I was shocked to discover this new way of thinking about art. However, I also encountered resistance. Most of works critiqued modern art and aimed to deconstruct classical forms. While materiality was evident in the pieces, I found few that explored the concepts of “carving” or “engraving.”

In essence, we seemed to lose the “language of sculpture” that emerges from the interplay of matter and form. For paintings, there’s a distinct “language of painting” created through the relationship between color and brushstroke. I questioned whether we could remove those emotions and sensations entirely. Losing the language of sculpture would mean losing the essence of what sculpture should be, which I found somewhat regrettable.