The Western-style building, the Japanese-style building, and the billiards room served as symbols of the Kyu-Iwasaki-tei Gardens. Although most of the Japanese-style building has been lost, it is rare for these buildings to remain in the gardens, allowing visitors to immerse themselves in the atmosphere of days gone by.

Kyu-Iwasaki-tei Gardens (Part 2)

In Search of Tokyo Serenity

No.009

This is a series of visits to gardens in Tokyo featuring photographs by photographer Norihisa Kushibiki and commentary by Miho Tanaka, curator at the Edo-Tokyo Museum.

The second part of the Kyu-Iwasaki-tei Gardens will introduce the architectural features of the Western-style building, the Japanese-style building, and the billiard room, with a guide by Isamu Yoneyama, architectural historian and researcher at the Tokyo Metropolitan Edo Tokyo Museum.

Photo: Norihisa Kushibiki

Story: Miho Tanaka (Curator at Edo-Tokyo Museum)

Cooperation: Tokyo Metropolitan Park Association

Energy of a young architect

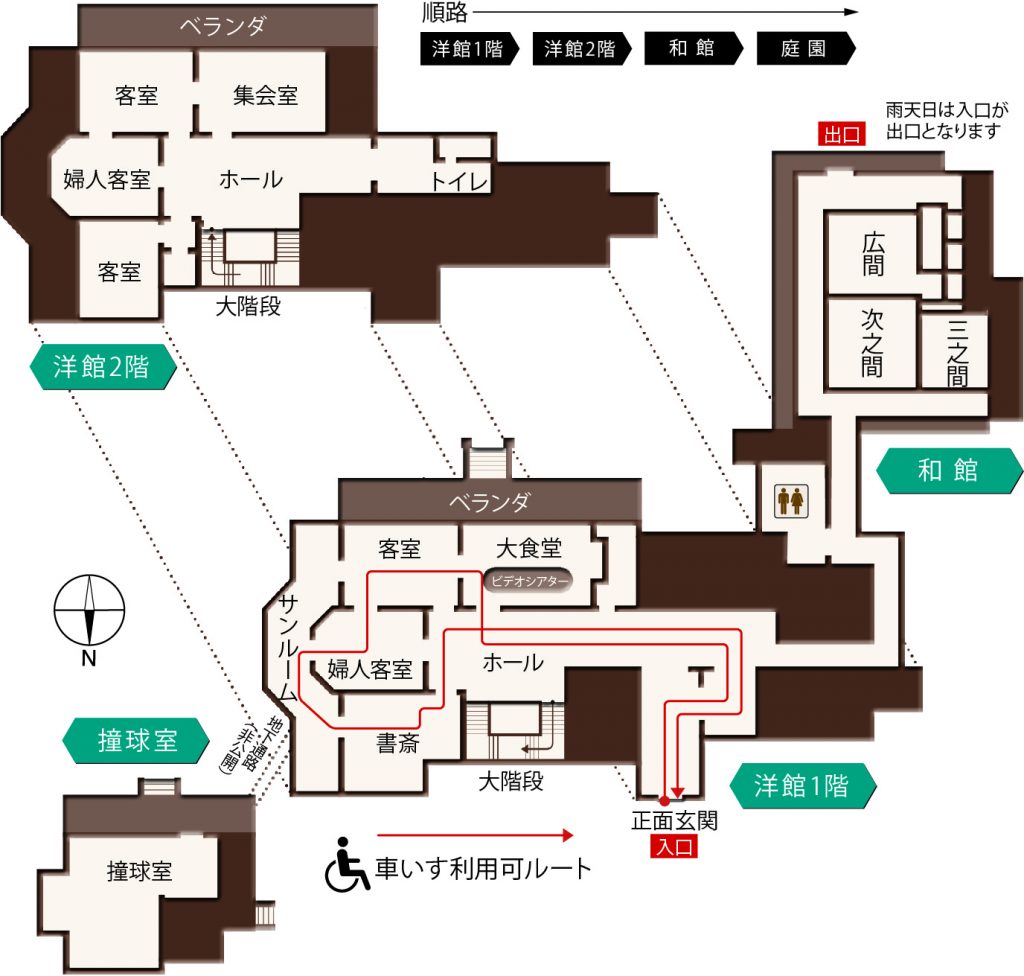

Right: Floor plan of the buildings in the Kyu-Iwasaki-tei Gardens

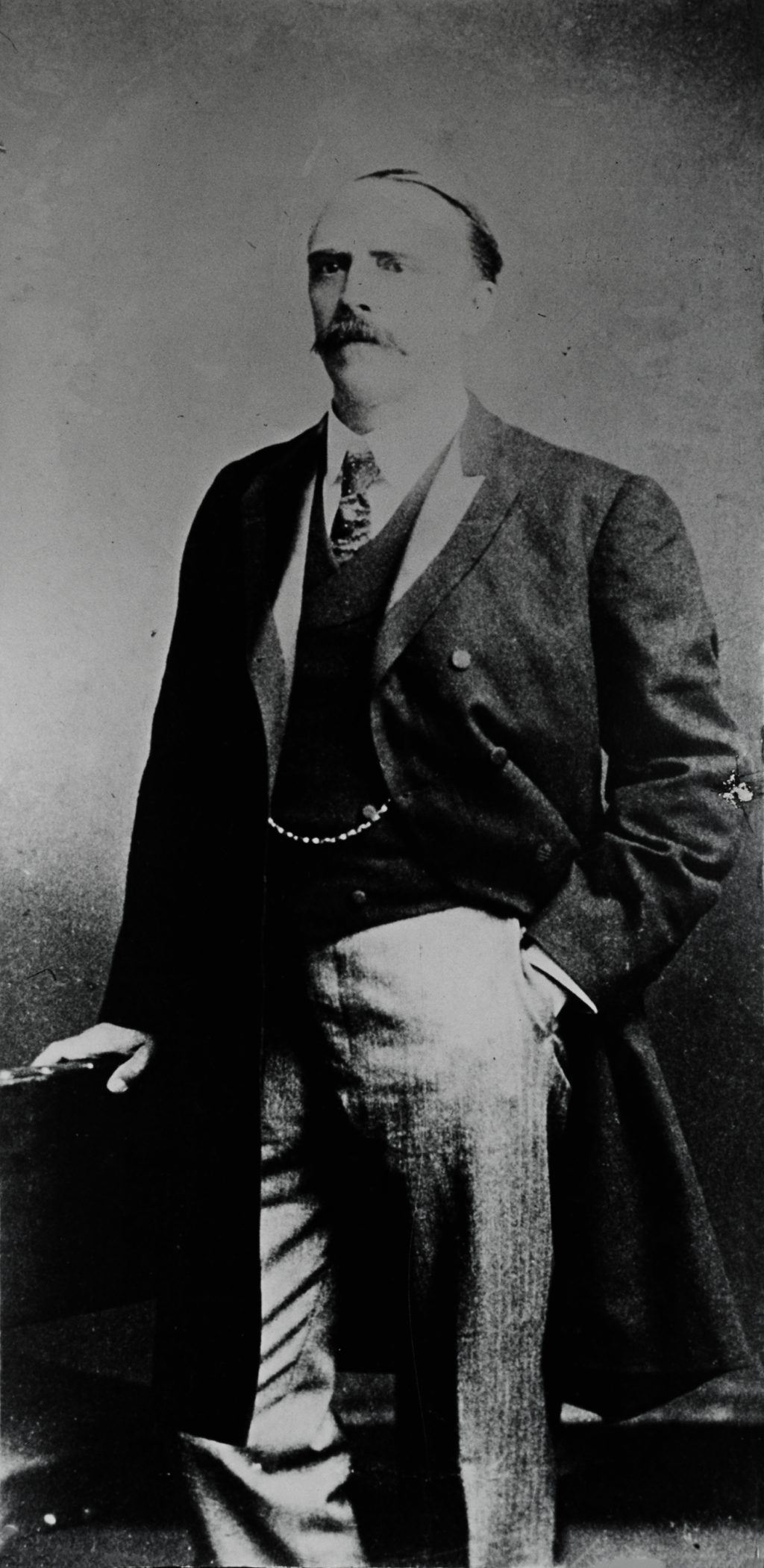

The British architect Josiah Conder, who designed the Western-style building and the billiard room, arrived in Japan in 1877 as a teacher at the Department of Architecture, Imperial College of Engineering (the predecessor to the Department of Architecture, Faculty of Engineering at The University of Tokyo). After working on the Rokumeikan banqueting house, his student Kingo Tatsuno became a professor in 1884, and Conder assumed an advisory role at Mitsubishi. He went on to design the Mitsubishi Ichigokan (now the Mitsubishi Ichigokan Museum) and many other significant works that represent modern architecture in Japan.

From “Tokyo Vintage Gardens”

The Western-style building is in the Jacobean style popular in 17th-century England. Why did Conder, a 19th-century architect, adopt the 17th-century style? I asked Mr. Yoneyama.

“When I visit Kyu-Iwasaki-tei, it often reminds me of Highclere Castle, the 1842 British estate featured in the television series ‘Downton Abbey.’ While the original Jacobean style was a thing of the past for Conder, the construction periods were close, leading to the possibility that they used Highclere Castle, known for its strong Jacobean revival character, as a reference,” Mr. Yoneyama replied.

From “Tokyo Vintage Gardens”

The Jacobean style is characterized by columns and railings that emphasize straight lines and sculptural decoration. On the exterior alone, carvings can be seen everywhere, including around doors and windows, and on pillars.

“Even the back of the balcony has a pattern, and you can see Conder's attention to detail in every corner,” said Yumi Suzuki, director of the Kyu-Iwasaki-tei Gardens Service Center.

From “Tokyo Vintage Gardens”

Mr. Yoneyama also expressed his admiration, saying, “The excessive amount of ornamentation is brilliant, as if Conder, who was in his mid-30s at the time, was overflowing with youth and vigor.”

There are indeed decorations everywhere, but they do not feel oppressive. The abundant use of wood gives the space a sense of warmth.

Brilliant and playful decoration

From “Tokyo Vintage Gardens”

Entering from the main entrance, the passageway to the Japanese-style building is on the right, and the main hall connecting the various rooms is on the left. The staircase, with its ornate carvings, is an example of Japan’s earliest atrium. The glossy wood texture creates a sense of dignity.

“When I was ill and out of work for a year and a half, this staircase appeared in my dream. I was encouraged, ‘I’m going to get well and climb these stairs!’ I was so encouraged. I am thrilled that my wish came true,” said Mr. Yoneyama.

The staircase with such a presence that it appears in Mr. Yoneyama’s dreams connects the first and second floors of the Western-style building.

From “Tokyo Vintage Gardens”

With the exception of the dining and meeting rooms where several people gather, most of the first and second floors are used as guest rooms, all of which are equipped with fireplaces.

“The fireplace is made of Japanese marble. In later years, a gas stove was installed to heat the room with radiant heat from a fireclay skeleton that burned bright red from the gas fire,” says Ms. Suzuki.

In the guest rooms on the second floor, the walls have been restored to their original Japanese kinkarakawashi (gold-embossed leather paper). Kinkarakawashi is a type of wallpaper created by adhering tin foil to washi paper, then adding texture through wooden blocks with carved patterns, followed by varnishing and coloring the surface. The Western arabesque pattern floating in gold is gorgeous. It would be hard to find a better place to see the precious gold-embossed paper on a large wall.

From “Tokyo Vintage Gardens”

The ladies’ guest room on the first floor is somewhat different from the others, with silk Japanese embroidery on the ceiling. Mr. Yoneyama explained that the decorations in this room are not of European origin.

“Conder was also fond of Islamic design. The tiles on the entrance and veranda have that look, and the first-floor ladies’ guest room also has a pointed Islamic arch called the ‘ogee arch,’” he added.

According to Terunobu Fujimori, an architect, architectural historian, and director of the Edo-Tokyo Museum, the Islamic style is often associated with tobacco, since tobacco was introduced to Europe via Islam. There is a possibility that this ladies’ guest room could have been a smoking room.

From “Tokyo Vintage Gardens”

Normally, a billiard room is built as a room within a Western-style building, but in Kyu-Iwasaki-tei, it is an independent room, connected to the Western-style building by an underground passageway. Usually, residents would have entered from the outside, and on rainy days, from the underground passageway.

“The separation of the billiard room, an independent space, lends it the ambiance reminiscent of a tea ceremony room,” said Mr. Yoneyama.

From “Tokyo Vintage Gardens”

According to Conder, the design is in the style of a Swiss mountain cottage, with a playful touch in the azekura-zukuri style like wood construction and “shingle” walls, which look like fish scales. This room is also covered with kinkarakawakami wallpaper.

Hospitality is where you see it

Let’s walk through the connecting corridor to move from the Western-style building to the Japanese-style building. More than a dozen Japanese-style houses were once connected by corridors, where many members of the Iwasaki family lived.

“Unlike most shoin-zukuri style buildings, it has deep eaves. Although the roof is large, it is made of two layers of roof tiles and copper sheets, giving it a light impression,” said Mr. Yoneyama. So, it is based on the shoin-zukuri style, but also incorporates a light design.

From “Tokyo Vintage Gardens”

In the existing large hall, there are paintings on sliding doors by Gaho Hashimoto, a Japanese-style painter of the Meiji Era. These paintings depict landscapes of the four seasons and Mount Fuji, intended to delight international guests.

From “Tokyo Vintage Gardens”

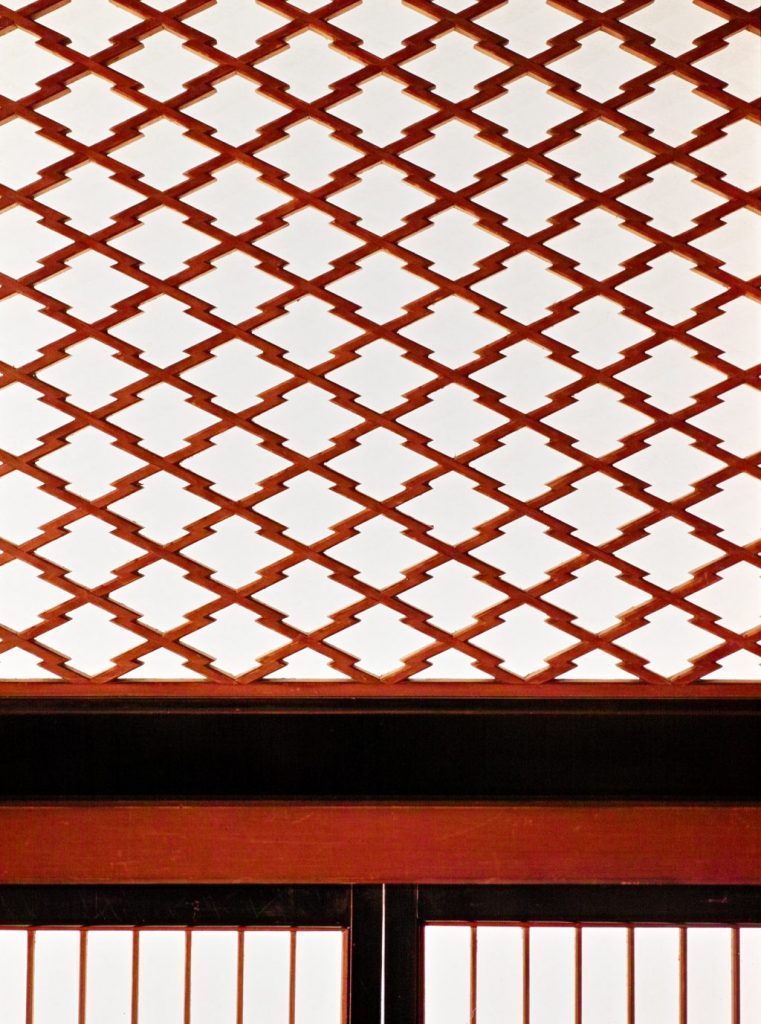

In the middle of the long corridor, near the back room, there is a bamboo joint ranma. The bamboo knot-like decorations at both ends are said to mark the rise in the prestige of the room after this ranma. Also, if you look closely at the ceiling, you will see that it is made of a single board from one end to the other.

Mr. Yoneyama told us, “The true hospitality is to show extravagance where it can be seen, so that only those who understand it can appreciate it.”

Although the Japanese-style building looks simple compared to the Western-style building, Mr. Yoneyama’s explanation made me realize that there are many elaborate features in the Japanese-style building.

Harmony of Architecture and Garden

For Mr. Yoneyama, Kyu-Iwasaki-tei is a familiar building that has become a spiritual home for his architectural research.

“Kyu-Iwasaki-tei has a three-tiered structure of the Western-style building, the Japanese-style building, and the billiard room, and is the most ornately decorated of the Conder architecture. Conder was the last architect who strongly believed in viewing the garden from the building. This is a rare place where both the building and the garden have been preserved, and I hope visitors will be conscious of that.”

In the past, I have mainly introduced strolling gardens with pond and streams with their varied topography, however, this time we had a different garden tour with three buildings of different styles, a spacious lawn garden and a tsuboniwa small garden.

Although there are few gardens where buildings still exist, gardens are essentially meant to be appreciated from within the buildings, and they are designed to align with the concept of the building, whether it serves as a family residence or for guest hospitality.

I was reminded once again to keep in mind that the idea of “gardens that are influenced by the presence of buildings,” as we appreciate them.

Japanese original text: Yasuna Asano

Translation: Kae Shigeno

Kyu-Iwasaki-tei Gardens

Address: 1-3-45 Ikenohata, Taito-ku, Tokyo

Hours: 9:00-17:00

Closed: Year end/New Year’s holidays

Admission: General 400 yen, 65 and over 200 yen

https://www.tokyo-park.or.jp/teien/en/kyu-iwasaki/index.html

Norihisa Kushibiki

Photographer. Born in Hirosaki City, Aomori Prefecture. Active mainly in the fields of advertising and editorial work. Provides portrait photography for numerous celebrities and prominent figures. Took private photos of Giorgio Armani and Gianni Versace. His work as an official photographer of the nine Tokyo metropolitan gardens inspired him to continue taking photos of traditional Japanese-style gardens as his life’s work.

Miho Tanaka

Curator at Edo-Tokyo Museum. Provides explanations of historical materials and delivers lectures on the theme of the relationship between people and flora, and specifically the art of gardening, during the Edo period. Tanaka conducts a course “Traditional Japanese Gardens x Area Guide,” which explores the history of classical gardens in Tokyo from the perspective of local characteristics.

Isamu Yoneyama

Researcher and architectural historian at the Edo-Tokyo Museum. Inventor of “Kenchiku Taiso (lit. architecture gymnastics),” a workshop for learning architecture. In addition to his academic activities, he is dedicated to spreading the joy of architecture appreciation in an easy-to-understand manner through media appearances and lectures. He is the editorial supervisor of “Shashin to rekishi de tadoru nihon kindai kenchiku taikan” (Modern Japanese architecture traced through photographs and history), 3 volumes, Kokushokankokai, “Sekai ga urayamu nippon no modernism kenchiku” (Modernist architecture of Japan, the envy of the world), Chikyumaru, among others. He received the Toumon Kenchikukai (Association of Waseda Architecture) Special Achievement Award (2009), the Japan Institute of Architects Golden Cubes Awards Special Prize (2011), and the Architectural Institute of Japan Education Award (Educational Contribution) (2013).

For more information about the course, please visit the Edo-Tokyo Museum website at

https://www.edo-tokyo-museum.or.jp/en/event/other-venues/ (in Japanese)

https://www.edo-tokyo-museum.or.jp/en/event/ (in Japanese)