The Former Yasuda Garden, Tokyo’s designated place of scenic beauty, is the nearest garden to the Edo-Tokyo Museum, and I often come here during break time. It is named after Zenjiro Yasuda the First, a businessman from the Meiji and Taisho periods and the founder of Yasuda Zaibatsu (a financial conglomerate).

The site is not too large, about 14,000 m2 (square meters), but it has an undulating terrain with an artificial hill. With elements of a Japanese garden—a pond, island, planting, such as pine trees, and rockworks—combined with Tokyo Skytree in the distance, the garden offers a symbolic scenery with the essence of both Edo and Tokyo.

Former Yasuda Garden

In Search of Tokyo Serenity

No.007

Photo: Norihisa Kushibiki

The series of articles introduces the allures of gardens in Tokyo with commentary by Miho Tanaka, curator at the Edo-Tokyo Museum.

This time, we visited the Former Yasuda Garden (Kyu-Yasuda Teien), located by the Sumida River in Ryogoku. The garden is abundant in water and greenery, offering a place of relaxation to the locals. What laid the foundation for it was a lofty aspiration of businessman Zenjiro Yasuda.

Photos: Norihisa Kushibiki, Shu Nakagawa

Commentary: Miho Tanaka (Curator, Edo-Tokyo Museum)

Collaboration: Sumida Tourism Association

Garden Imbued with Essence of Edo and Tokyo

Photo: Shu Nakagawa

Photo taken by Ms. Tanaka in 2007

Walking Along Tidal Waterside

The uniqueness of the Former Yasuda Garden can be found in its waterside landscape. The garden used to be a tidal, stroll-type garden, drawing water from the Sumida River. Today, the pond’s water level is artificially controlled to recreate the movement. Back in the day, the Sumida River ran closer to the sea, and its water level changed with the Tokyo Bay’s tide. When the water level is lower, the pond’s stones are exposed more, transforming the landscape’s impression.

The foot of the stone lantern is filled with stones called ishihama (stone shore) to emulate waterside. From there, stepping-stones are laid out in sequence along the pond’s perimeter, and you can walk on them when the water level is low. But you have to be careful not to slip on the stones as they are covered with moss from being in water.

You can come close to the waterside and spend some time observing creatures like turtles, seagulls, and water striders. On that day, I was surprised to find a shrimp. I had never seen it before.

There used to be many gardens that had a tidal pond, and they all had elaborate water features. Today, some gardens, including the Hama-rikyu Gardens and the Former Yasuda Garden, recreate tidal ponds in Tokyo, and only Hama-rikyu actually uses seawater.

Accentuated by Stones and Greenery

Behind a grove is an artificial hill, which offers a different scenery from the waterside. Along the hill, there are two large stones placed on both sides of the garden path. I think they are the garden’s keystones.

Rockworks are critical in garden design. The placement of stones in a limited space can change a garden’s visual appearance, like spatial expansiveness and perspective. These large stones can be seen from the other side of the pond, with an island in between. I think their role is to refine the garden’s landscape. Otherwise, you wouldn’t put such large pieces in the middle of a path.

Another scenic feature of a Japanese garden, along with water and stones, is planting, which changes with the seasons. I don’t think this garden has cherry trees, but it has flowers and trees you don’t usually find elsewhere, like azaleas, camellias, and fragrant olives, adding different colors. You will find picturesque views around the arched bridge with beautiful autumn leaves. When the broad leaves fall off the trees, rockworks become more visible, and in winter, pine trees on the island are protected from snow with ropes. The garden’s ever-changing scenery in spring, summer, fall, and winter is something you can look at every day and never get tired of.

There are several parks around the Sumida River, but it is rare to find a place where water and greenery come together in such a natural way. That is probably why various living creatures gather here.

Historic Spots that Mark Garden’s History

As you proceed along the path to the back of the garden, you came to an open area. It may seem like there is nothing special here, but there are important historical spots that mark the Former Yasuda Garden’s history.

First are Komadome Inari and Komadome Ishi, which remind us of the Honjo Yokoami-cho of the Edo period. During the reign of the third shogun, Iemitsu, the Sumida River did not yet have the Ryogoku Bridge, and only the Senju Ohashi Bridge connecting present-day Kita Senju and Minami Senju. The only way to cross the river from around there to the other side was by boat. In 1631, a major flood occurred on the river. Iemitsu had his men survey the damage, but the muddy waters blocked their way and prevented them from doing so. So, Abe Bungo-no-kami Tadaaki crossed the river on horseback and surveyed the damage. During his duty, he stopped his horse and rested at Komadome Ishi. Komadome Inari was erected by people living in the area to honor Tadaaki’s achievement.

Another spot indispensable to discussing the Former Yasuda Garden’s history is the stone monument inscribed “Shisei-kinken.” “Shisei” means to be fair and sincere, and “kinken” means to be diligent in your work and not spend redundantly (waste money). The phrase conveys the life principles of Zenjiro Yasuda, the former owner of this garden. It is an important spot that tells the story of the Former Yasuda Garden in Edo-period Tokyo.

Zenjiro Yasuda’s Ambition

Zenjiro Yasuda left his hometown, Toyama, at the age of 17 and moved to Tokyo. In 1864, he opened the exchange store Yasudaya (bank) in Nihonbashi. Yasudaya quickly became one of the leading financial institutions in Tokyo and later expanded into the life and non-life insurance business. Many of the companies Zenjiro founded became the predecessors of various companies, including Mizuho Bank and Meiji Yasuda Life.

The current site encompassing the Former Yasuda Garden, Yasuda Gakuen Junior & Senior High School, and the Fraternity Memorial Hospital was occupied by the residence of Honjo Inaba-no-kami Munesuke, the lord of the Kasama domain in Hitachi Province during the Edo period. It is said that the tidal pond fed by the Sumida River was already there, but details of the garden have not been passed down. After the Meiji Restoration, the site became the residence of Marquis Ikeda, the former lord of the Bizen Okayama domain and, in 1891, the property of the Yasuda family.

According to newspaper articles of the time, the Yasuda residence hosted guests from Japan and abroad, including top Japanese political and business figures and honored guests from Qing China (present-day China), often providing receptions related to state diplomacy, like those hosted today at the Akasaka Palace, a state guesthouse. Receptions included some unexpected features, such as a beer hall, shiruko (sweet adzuki-bean soup with rice cake) shop, oden restaurant set up in the garden, as well as a Lion Dance and ball-balancing performance as entertainment.

Indeed, one of the reasons the Yasuda family, the Iwasaki family, who owned the Kiyosumi Garden and the former Iwasaki House Garden, and other businesspeople owned luxurious residences was to host guests.

In 1921, Zenjiro approved a plan advocated by the mayor of Tokyo City, Shinpei Goto, and decided to donate his residence and garden in Honjo Yokoami-cho to the city. He also donated 3.5 million yen to the Tokyo Institute for Municipal Research for the construction of Hibiya Public Hall and Honjo Public Hall (later Ryogoku Public Hall).

Zenjiro had a policy of investing funds in projects of high public interest. That meant, on the contrary, that he did not spend money on projects that were not beneficial to the public. Furthermore, he cherished the idea of amassing secret acts of kindness and did not make a big show of them. Perhaps this backfired on him, and in the same year, he fell victim to an assassin’s dagger.

Overcoming Earthquake and War Damage

After Zenjiro’s death, the Yasuda Residence and Garden came under the jurisdiction of the City of Tokyo, but a sudden development awaited them.

In 1923, the Great Kanto Earthquake struck. The neighborhood residents evacuated with their household goods to the site of Rikugun Hifuku Honsho (an army uniform factory, now Yokoamicho Park) next to the Yasuda Residence, where a firestorm claimed some 40,000 lives.

The firestorm also damaged the Yasuda Residence, and Zenjiro’s fourth son and his wife were killed. The garden, too, was devastated, except for the contours of the undulating land and masonry. In response to this earthquake, temporary shelters were built on the grounds of the Yasuda Residence to house the victims free of charge.

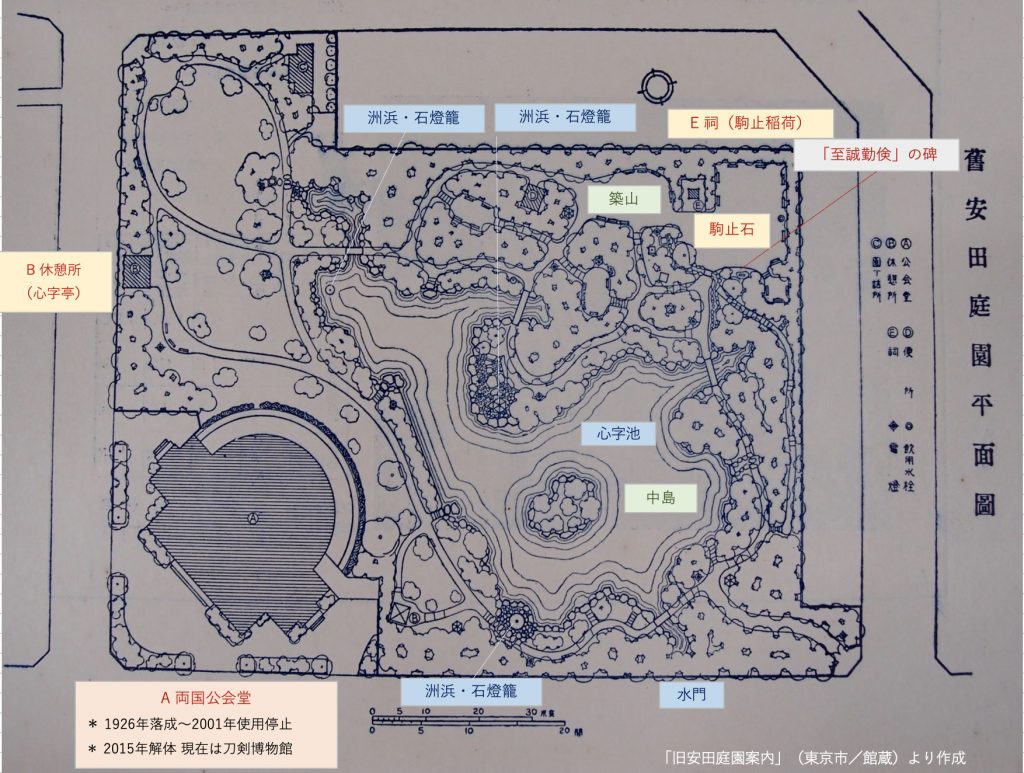

After restoration work by the City of Tokyo, the Yasuda Garden was opened to the public in 1927, finally realizing Zenjiro’s wish. The garden’s brochure issued at that time shows its appearance almost the same as it is now. It includes the fee for using the garden, so I am guessing it was available for use with the Ryogoku Public Hall. After the war, the garden was confiscated by the U.S. military for a time but was returned in 1955 and reopened to the public the following year.

After the war, the garden underwent an ordeal once again. In 1962, the Sumida River was revetted in preparation for a flood. Until then, the river and pond had been gently connected, but the water flow was stopped, and the quality of the water deteriorated, leading to the death of trees in the park. However, the garden was largely renovated from 1969 to 1970, becoming an artificial tidal, stroll-type garden, as it is now, which resulted in the improvement of the environment.

Thanks to these efforts, in 1996, the Former Yasuda Garden was designated a place of scenic beauty by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government.

In the 2000s, another conservation and management plan was implemented: the color of the bridge was changed from red to the original stone color, a rest area called Shinji-tei was added, and the garden paths’ gravels were made easier to walk on. Following the demolition of the adjacent Ryogoku Public Hall and the opening of the Japanese Sword Museum, the garden retains the appearance it had when it first opened in the early Showa period. I am impressed by how the garden has been preserved according to Zenjiro Yasuda’s will.

Ryogoku’s Hidden Gem

The Former Yasuda Garden has an open atmosphere of shitamachi. I often see people taking a walk first thing in the morning or eating lunch on the bench, even on weekdays. It is also used for taking wedding photos. It is such a cozy garden that I have always wished I could work here. However, many people are probably unaware of its existence, as it is buried among the surrounding facilities, such as the Edo-Tokyo Museum, Ryogoku Kokugikan, and the Sumida Hokusai Museum.

The Former Yasuda Garden is small but well-defined, offering a variety of views and a formal Japanese garden style. Visitors can enjoy looking at the flowers and greenery and admiring the creatures even without knowing Japanese garden rules. It is a place where you can take a breather, but it is also a profound garden imbued with the way of life of an industrialist who contributed to modern society.

〈The End〉

Photo: Norihisa Kushibiki

Article composition: Yasuna Asano

Translation: Erica Sawaguchi

Former Yasuda Garden

Address: Yokoami 1-12-1, Sumida-ku, Tokyo

Hours: 9:00 am–7:30 pm (April–September), –6:00 pm (October–March)

Closed: Year-end and New Year holidays

Admission: Free

https://visit-sumida.jp/spot/6085/(in Japanese)

Norihisa Kushibiki

Photographer. Born in Hirosaki City, Aomori Prefecture. After graduating from university, he worked in the fashion business before moving to Milan, Italy. While there, he met artists in a variety of fields and began taking photographs. After returning to Japan, he worked as a photographer, mainly in the commercial and editorial fields. He has shot many portraits of celebrities, including private photos of Giorgio Armani and Gianni Versace. He has continued to photograph gardens as his life’s work since serving as the official photographer of the nine Tokyo Metropolitan Gardens. Invited to participate in the 6th International Biennale of Photography in Italy. Selected for the 19th International Biennial of Graphic Design Brno (Czech Republic).

Miho Tanaka

Curator at the Edo-Tokyo Museum, Tokyo. She was in charge of the special exhibition Hanahiraku Edo no engei (Flowering horticulture in Edo). She has given lectures and commentaries on horticulture in the Edo period and on the relationship between plants and people. She also gives a lecture, "Garden x Area Guide," which discusses the origins of gardens in Tokyo from the characteristics of the surrounding areas.

For details about the lecture, visit the Edo-Tokyo Museum website:

https://www.edo-tokyo-museum.or.jp/en/event/other-venues-culture/