Yanagisawa Yoshiyasu rose to power at an extraordinary pace, earning the favor of the fifth shogun, Tokugawa Tsunayoshi. At the age of 30, he was appointed “soba yonin,” a highly trusted chamberlain serving by the shogun’s side, and six years later, he became “roju-kaku,” the highest-ranking government official overseeing the shogunate’s administration. While period dramas often portray him as a villain, the reality was quite different—his rapid rise may have seemed unusual or even astonishing to other daimyo at the time.

A theme park of waka poetry: Rikugien Gardens (Part 2)

In Search of Tokyo Serenity

No.011

This series offers an engaging exploration of Tokyo’s gardens, featuring photographs by Norihisa Kushibiki and commentary by Miho Tanaka, curator of the Tokyo Metropolitan Edo-Tokyo Museum.

Rikugien is a tranquil garden that recreates the world of waka poetry. What kind of person was Yanagisawa Yoshiyasu, the owner of the gardens? In this second part, we will explore how the garden evolved over time under different owners and the roles it played throughout history.

Photographs: Norihisa Kushibiki

Commentary: Miho Tanaka (Curator, Tokyo Metropolitan Edo-Tokyo Museum)

Cooperation: Tokyo Metropolitan Park Association

The life of Yanagisawa Yoshiyasu

From “Tokyo Vintage Gardens”

Rikugien frequently welcomed visits from the shogun and his family, with elaborate arrangements made for their entertainment. In 1703, when Tsunayoshi’s eldest daughter, Princess Tsuru, visited the garden, Yoshiyasu orchestrated a remarkable spectacle: as she stepped into the garden after being warmly received at the residence, a pair of cranes (tsuru), matching her name, suddenly took flight—a carefully planned moment.

Yoshiyasu also maintained close ties with the imperial court, partly due to the noble lineage of one of his concubines. He even presented drawings of Rikugien to Emperor Emeritus Reigen, who was so impressed that he selected twelve particularly scenic spots within the garden—referred to as the “Junikyo Hakkei” (Twelve Scenic Views)—and commissioned his courtiers to compose waka in their honor. The emperor then returned these poems as a gift, an exceptional gesture of recognition for Yoshiyasu, who was not of shogunal rank.

From “Tokyo Vintage Gardens”

Like Yoshiyasu, his grandson Nobutoki also loved Rikugien so much that he wished to retire as soon as possible and move to Rikugien. However, not everyone born into the Yanagisawa family shared the same love for the garden. If a lord with an interest in gardens took over, they would take care of it; if not, the space would be left untouched while still being maintained. It seems that Rikugien was no exception to this pattern.

Iwasaki Yataro’s Rikugien

Many daimyo gardens underwent significant transformations during the transition from the Edo to the Meiji periods. Due to the Meiji government’s land confiscation, the territories of daimyo were seized. As a result, the Yanagisawa family had to part with their estate, and Rikugien seems to have been left unattended.

From “Tokyo Vintage Gardens”

Later, in 1878 (Meiji 11), Iwasaki Yataro, the founder of Mitsubishi, purchased Rikugien for use as a private residence. During the restoration work carried out by the Iwasaki family, tens of thousands of trees were replanted. This suggests that the garden may have been in poor condition. As I mentioned in the episode about Kiyosumi Gardens, Yataro was a great lover of stones, but in Rikugien, the prominence of stones is not as strong. Several structures, such as tea houses and storehouses, were built, but there were no major renovations that disrupted the overall contours of the garden. It seems that Yataro understood the concept of Rikugien and the passion that Yanagisawa Yoshiyasu had for the garden, maintaining it with great care.

In addition to Rikugien, the Iwasaki family acquired the lands of three other daimyo families in the surrounding area and developed them into the Komagome residence. In 1905 (Meiji 38), a celebratory banquet was held to commemorate the victory in the Russo-Japanese War, with records stating that 6,000 guests were invited.

From “Tokyo Vintage Gardens”

Rikugien was donated to the city of Tokyo by the Iwasaki family in 1938 (Showa 13) and opened to the public the same year. A monument expressing gratitude for this donation is one of my favorite historical landmarks. Two years later, it was designated a Janan’s Place of Scenic Beauty, and in 1953 (Showa 28), it was designated a Special Place of Scenic Beauty.

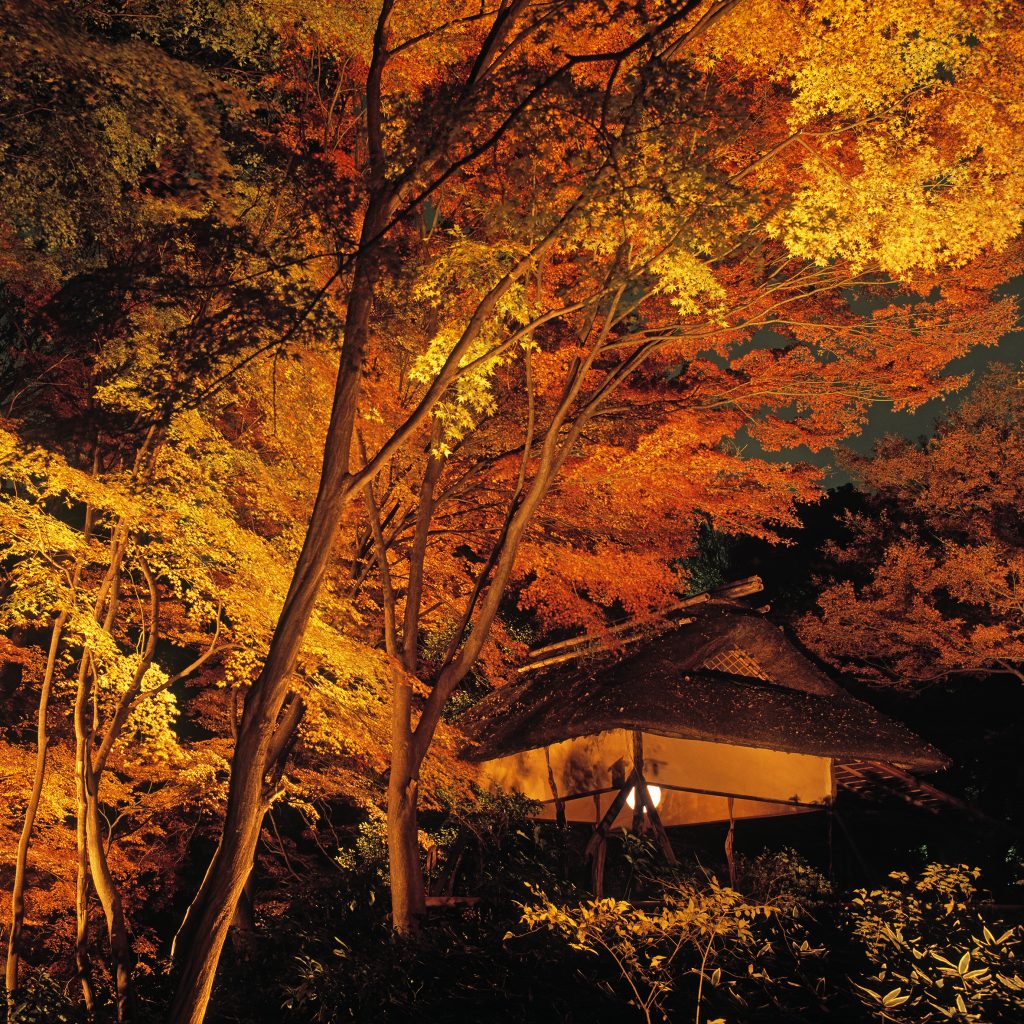

The weeping cherry tree was planted in the 1950s. It stands about 15 meters tall and spreads about 20 meters wide. It blooms a little earlier than the Somei Yoshino cherry trees, typically in late March. While it does not bloom during the colder months, its graceful branches are visible. According to the garden staff, during the cherry blossom season, the gardens once saw around 30,000 visitors per day. Today, alongside the autumn foliage, it has become one of the signature seasonal highlights of Rikugien.

Preserving the gardens for the future

During the Edo Period, many of the daimyo gardens were left to deteriorate if their owners had no interest in maintaining them. There are even articles from old newspapers that describe how trees and stones from once-celebrated gardens were priced and sold. Considering this, we can truly appreciate that, thanks to the Iwasaki family’s careful management and their donation of the garden to the city of Tokyo, we are able to enjoy Rikugien today, which still retains the traces of its Edo-era charm.

From “Tokyo Vintage Gardens”

To preserve and maintain the concept of a garden through changing times and seasons requires a long-term vision, careful planning, and tremendous effort. These outdoor cultural assets, such as gardens, necessitate rules and manners for us to appreciate them properly. While it may seem strict at times, these measures are crucial to preserving the garden’s quality as a cultural heritage and passing it on. With that in mind, I hope you will continue to enjoy the seasonal landscapes of the garden in your own way.

Japanese original text: Yasuna Asano

Translation: Kae Shigeno

Rikugien Gardens

Location: 6-16-3 Hon-komagome, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo

Hours: 9:00 a.m.–5:00 p.m. (admission until 4:30 p.m.)

Closed: Year-end and New Year holidays

Admission: General 300 yen, 65 and over 150 yen

https://www.tokyo-park.or.jp/teien/en/rikugien/

Norihisa Kushibiki

Photographer. Born in Hirosaki City, Aomori Prefecture. After graduating from university, he worked in the fashion business before moving to Milan, Italy. While there, he met artists in a variety of fields and began taking photographs. After returning to Japan, he worked as a photographer, mainly in the commercial and editorial fields. He has shot many portraits of celebrities, including private photos of Giorgio Armani and Gianni Versace. He has continued to photograph gardens as his life’s work since serving as the official photographer of the nine Tokyo Metropolitan Gardens. Invited to participate in the 6th International Biennale of Photography in Italy. Selected for the 19th International Biennial of Graphic Design Brno (Czech Republic).

Miho Tanaka

Curator at the Edo-Tokyo Museum. She was in charge of the special exhibition “Hanahiraku Edo no engei” (Flowers in Bloom: The Culture of Gardening in Edo). She has given lectures and commentaries on horticulture in the Edo Period and on the relationship between plants and people. She also gives a lecture, “Garden x Area Guide,” which discusses the origins of gardens in Tokyo from the characteristics of the surrounding areas.

For details about the lecture, visit the Edo-Tokyo Museum website:

https://www.edo-tokyo-museum.or.jp/en/event/other-venues-culture/