Before the participants entered the exhibition gallery, they heard a lecture by Hiroko Tsuda, curator of the Edo-Tokyo Museum. They learned that the worksheet is a tool to enjoy viewing exhibitions. Not just for fun, this tool prompts viewers to ask, “What’s this?” and say, “I understand this!”

The museum provides three types of worksheets, for elementary, junior-high and high school students. Each requires 60 minutes to complete. Since the participants of the day were teachers at elementary schools, they tried the version for elementary school students.

There are four items:

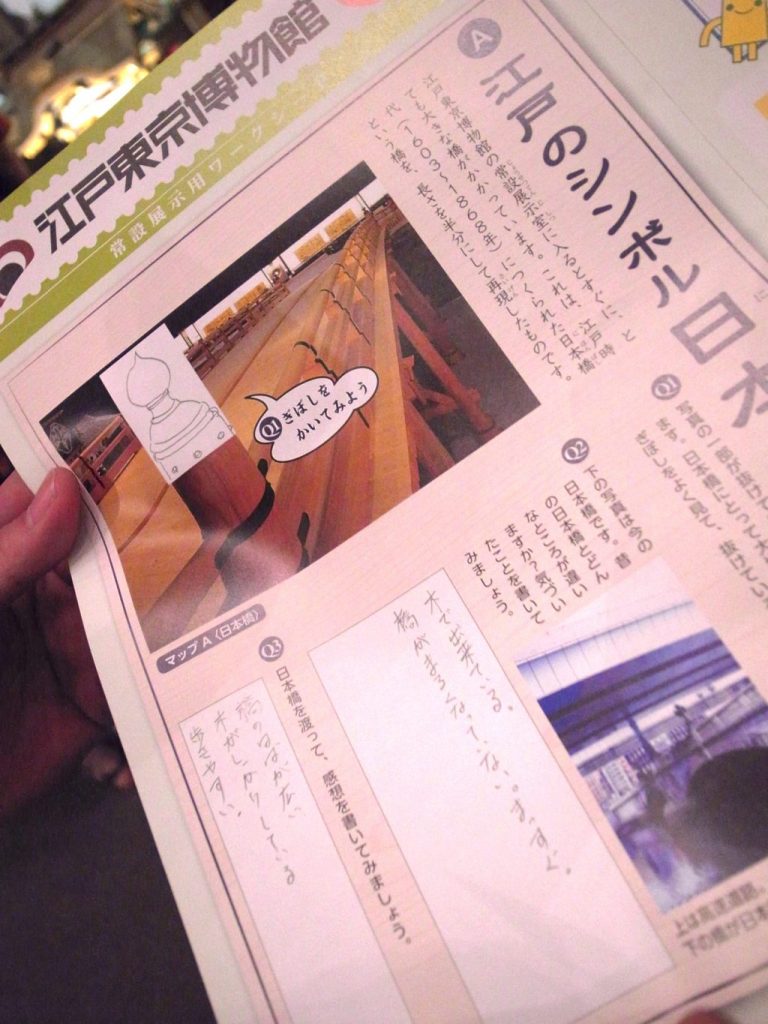

- “Nihonbashi Bridge,” a symbol of Edo. The worksheet encourages students to draw its ornamental cap and add their review comments.

- “Let’s ride in a Daimyo palanquin.” Daimyo in the Edo Period traveled by palanquin on journeys lasting more than 20 days. The participants fill out the worksheet with their comments.

- “Let’s try” encourages them to lift a firefighter bar and a chest for keeping gold coins, or to carry a night-soil bucket, to know what life was like in Edo.

- “Compare the tools now and then” informs the student about what washing machines and rice cookers looked like in the Edo Period.

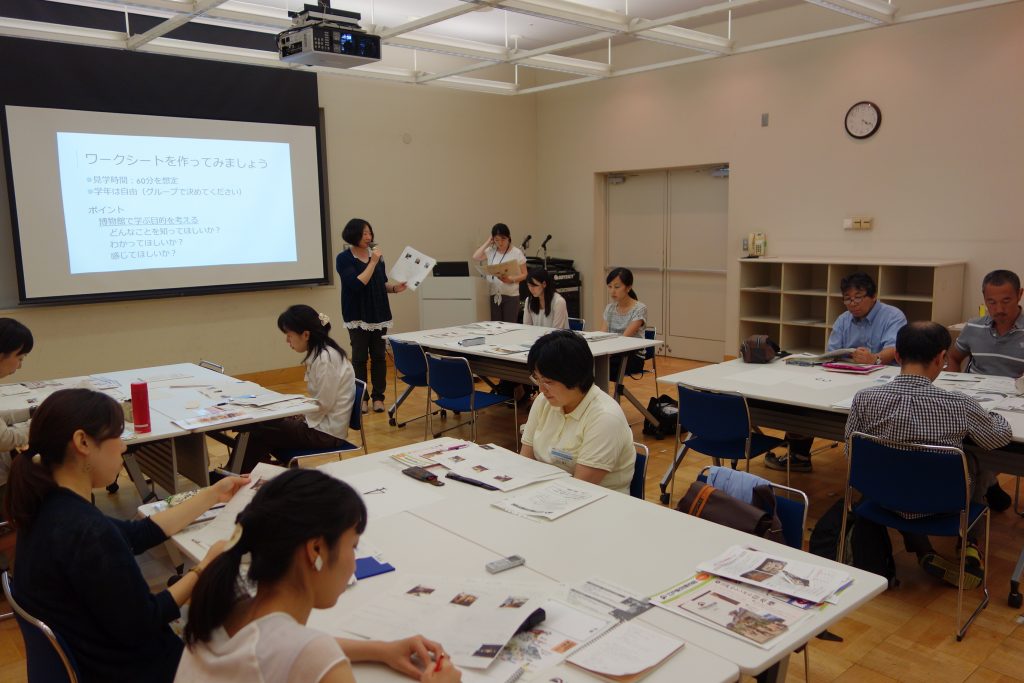

The permanent exhibition area covers about 9,000 square meters and displays people’s everyday lives and history from the Edo Period to today. It’s not easy for elementary school students to learn everything during the limited time. So, the important point is to set viewing hours and number of questions. “Once the worksheet is made in line with children’s interests and related to everyday education programs, it can guide them toward an enjoyable program,” Tsuda told the participants.

Ms. Michiko Tateyama and Ms. Ayumi Hattori started a discussion in the corner of the exhibition gallery. “Let’s make the worksheets with items directly related to children’s everyday lives,” “I think it would be better not to have a one-by-one Q&A, but rather describe things that children discover.” They quickly settled on the structure in just five minutes. “If the number of queries are fixed, children may look for the locations first. But it’s better if the sheet encourages them to take note what they found,” Ms. Tateyama commented. “It would be good to give them an interesting point. For instance, the Daimyo palanquin. They can try to get inside and imagine what it was like to travel that way for more than 20 days at a time,” said Ms. Hattori.

The teachers returned to the study room and wrapped up their work to make their sheets in about 30 minutes.

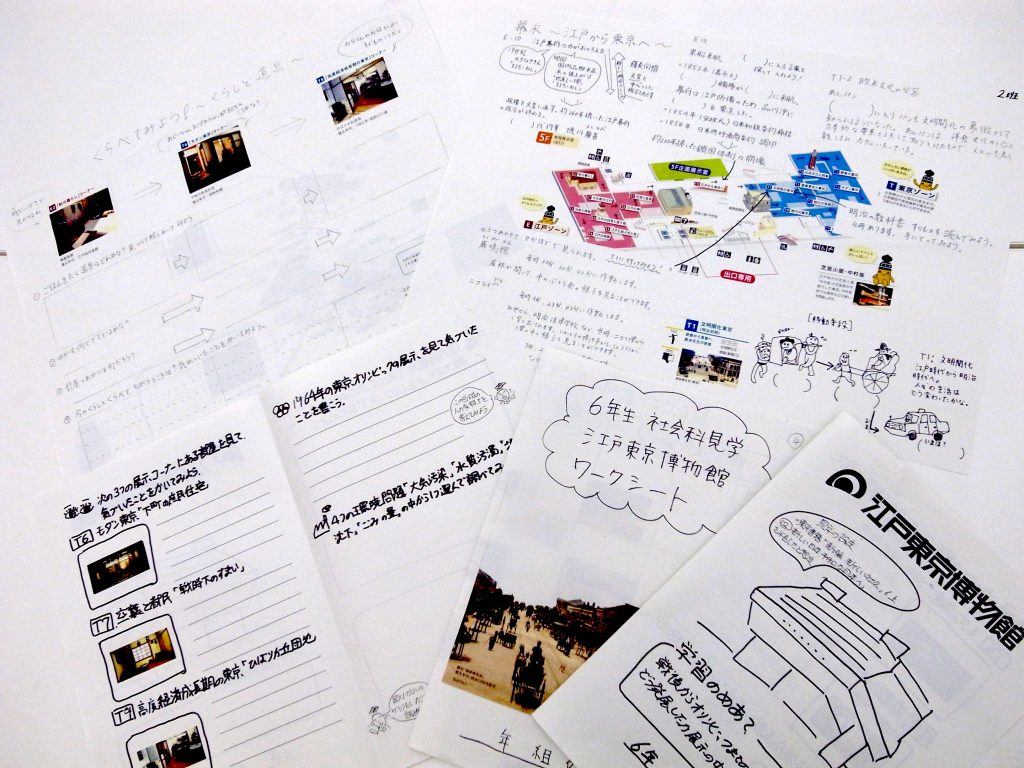

On A3 size paper, they drew a framework and pasted cutout photos, visual images and other materials.

Worksheets made by all the groups were copied and distributed to all participants. They went back to the exhibition area and worked on the worksheets. After that, they evaluated their work among themselves. The worksheets of Ms. Tateyama and Ms. Hattori were well evaluated by other groups. However, a shortage of time meant some items were left blank. It was suggested that these parts be homework.

The program ended. Ms. Hattori commented that this kind of in-depth program is very rare and important. “I was also stimulated because of the group work,” she added. Ms. Tateyama said, “Usually, visits to facilities to observe give us chances to go through the facility one time only. Or, just look through their pamphlets and websites. This program involved hours. That was valuable. I was also impressed by other groups’ worksheets.”

Tsuda commented that she learned a lot from the program on the day because the participants were teachers who communicate with children every day.

This program will be featured during the summer months next year.