──How did you become fascinated by woodblock prints?

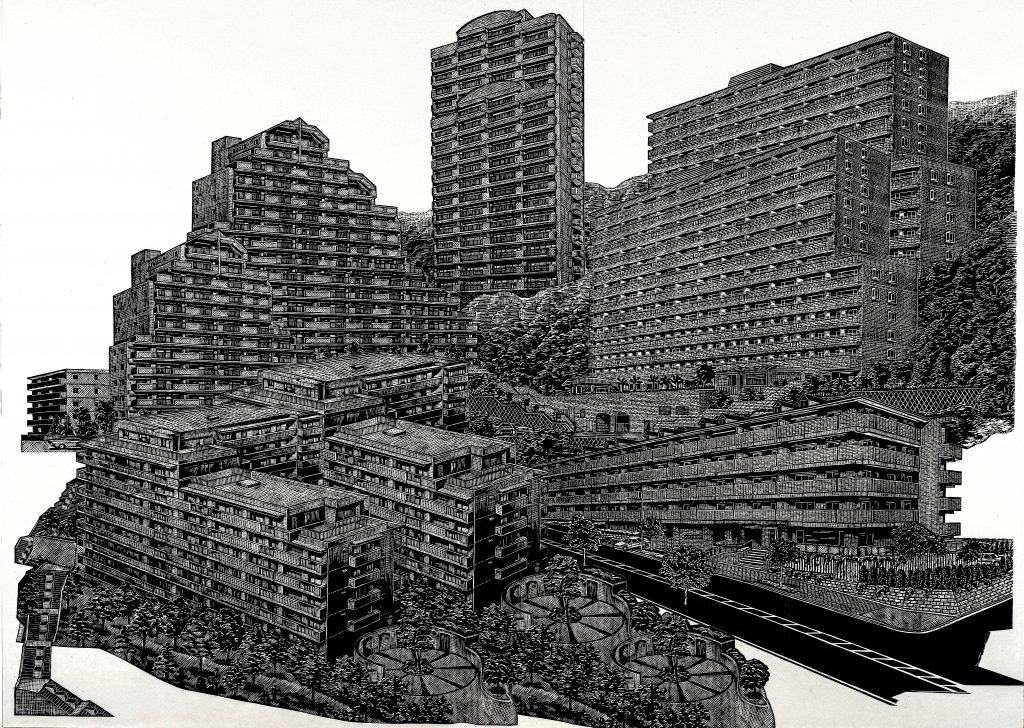

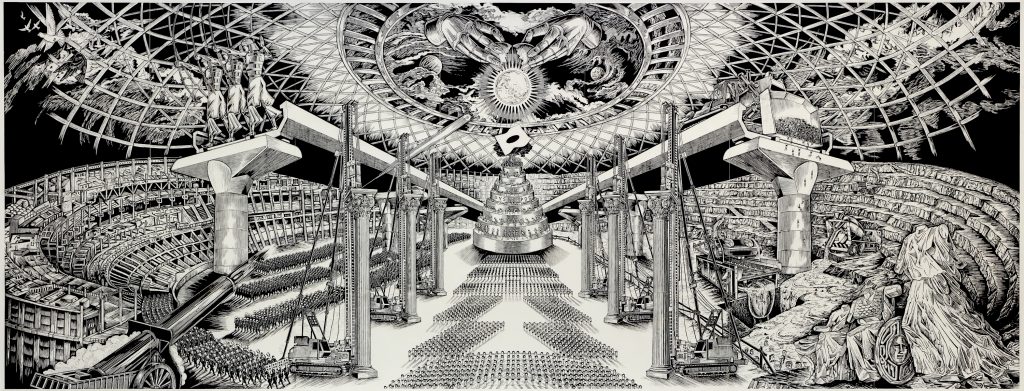

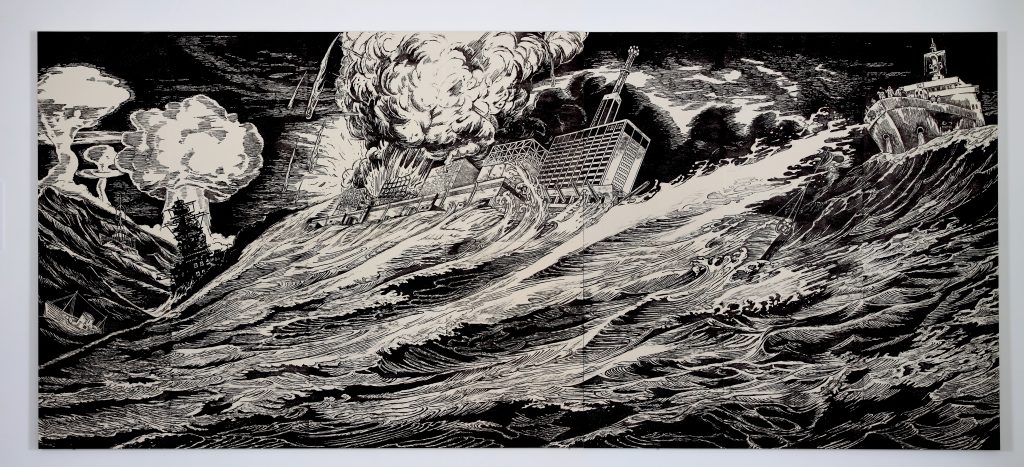

My grandfather was a head clerk at an artists’ supplies shop of Japanese-style paintings, and we had books of Japanese-style paintings and ukiyo-e, which I often looked at. However, it was not the ukiyo-e woodblock prints that attracted me. When I was in high school, I fell in love with the illustrations of Taisho-period poetry books by poets like Sakutaro Hagiwara and Hakushu Kitahara. Although the illustrations for the poetry books and ukiyo-e are both woodblock prints, they are completely different. The Taisho-period works are called sosaku-hanga (creative prints), which engrave imagined landscapes on blocks. I was surprised and inspired to see such an expression and wanted to try it myself.

──Did you start producing works in high school?

No. At the part-time high school I attended, the art teacher specialized in woodcarving, I think, and the name of the course was “woodcarving,” not “art” (laughs). We used chisels, but we created wooden sculptures, not woodblock prints. It wasn’t until after graduating from high school and entering Musashino Bijutsu Gakuen (closed in 2018) that I learned printmaking in earnest. Back then, I could only think of art universities to study printmaking, but when I read akahon (a book containing past entrance exams for a university) my mother bought me, I had no idea what was written. I gave up on art universities and looked for other schools. In the end, I found Musashino Bijutsu Gakuen, which only required an interview to get in.